Harry Soulsby photographed in full drawing room dress in 1928. Photo courtesy of Hilda Treherne, Commander Soulsby’s daughter.

Although he was a modest man with no taste for the spotlight, Henry (Harry) Wickens Stephens Soulsby certainly left his mark on the Royal Canadian Navy, and on the coastline of British Columbia.

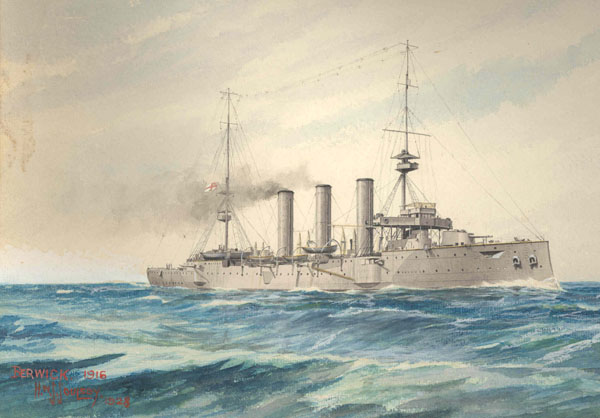

In addition to serving as a sailor in two World Wars, Commander Soulsby was a gifted artist and craftsman. He designed and illustrated recognition certificates for Canadian sailors. His distinctive signature and the energy of his artwork are featured in many such certificates issued to Canadian sailors over the years to mark their passage across important geographical parallels (known as “Crossing the Line”). He also designed ship’s badges.

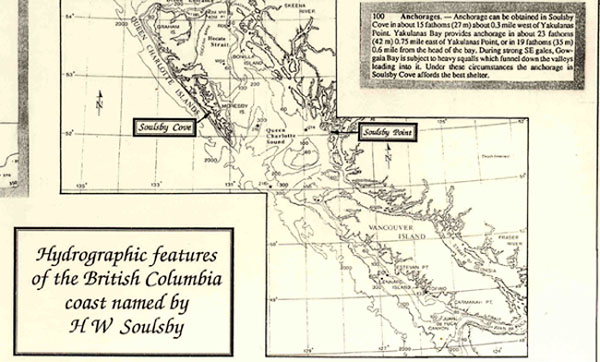

Harry Soulsby also volunteered for the Hydrographic Surveying Service of the Royal Navy after World War I, and Soulsby Cove on the Queen Charlotte Islands, and Soulsby Point in Hunter Channel, both chart locations in British Columbia, are named for him.

Henry Wickens Stephens (H.W.S.) Soulsby was born in Toronto, Ontario, in 1896. When he was a year old, his father moved the family back to the city of Hull in England, from which they had emigrated to Canada. While Harry was at school near Hull, he began his lifetime association with wood carving. At age nine, as the result of a school class, he started chip carving and liked it well enough to continue during his holidays. His ability was such that his father sent him for lessons in relief carving at the age of twelve. He also attended Trinity House Navigation School and originally intended to follow in the family tradition by joining the Merchant Marine.

Areas on the BC coast named by Harry Soulsby. Image courtesy of Hilda Treherne, Commander Soulsby’s daughter.

In 1912, Harry Soulsby returned to Canada alone to stay with relations in Almonte, Ontario. He was just 15. He succeeded in passing the notoriously tough 3-day examinations to enter the newly established Royal Canadian Naval College in Halifax, Nova Scotia, placing fourth out of 20 candidates. With characteristic modesty, he later recalled his success thus: “It was quite a surprise to my parents and teachers when I passed the entrance exam …”

After borrowing money from his uncle to attend Naval College in Halifax, he joined a class of 10 Navy Cadets. He was extremely shy and would have preferred doing algebra to attending the compulsory afternoon teas with the local girls, held every month to help socialize the young cadets. In his 22 months as a cadet he was expected to develop qualities of initiative, ambition, aggression and even arrogance, all thought to contribute to the leadership skills of a naval officer.

In February 1916, Harry Soulsby, by then an Acting Sub-Lieutenant, went to his first Canadian ship, the original STADACONA, an ex-American steam yacht of ancient vintage. In February 1917, he and his fellow students from the naval college were sent to England. All of them asked for, and were sent to, destroyers. He served in HMS Jackal for eight months in the English Channel and approaches, and for 18 months in the Mediterranean.

After WWI, he was sent to England again to serve in the Royal Navy, as there was little or no activity in the Royal Canadian Navy at the time. In 1920 he married his Halifax sweetheart, Gladys Cunningham, who travelled to England for their wedding. Harry Soulsby eventually gravitated to the Hydrographic Surveying Service of the Royal Navy, “having” to use his own phrase, “a yen for that sort of thing”.

He worked for three and a half years in the surveying service, and was, as far as is known, the only RCN officer to do so. His work took him up and down the east coast of England, where his artistic ability was useful in working with and preparing charts.

In 1923, while he was doing a survey of Bermuda harbour, he was ordered to return to Canada for service in Halifax. He served there and in Ottawa and Esquimalt. While in command of the minesweeper HMCS ARMENTIERES, he piloted her 42,180 miles along the BC coast, patrolling and surveying – and all, he later recalled, “at no greater speed than nine knots!”

Between 1930 and 1940 Harry Soulsby commanded various HMC ships, including the minesweeper HMCS COMOX. In 1940, after a mediocre appraisal, he stated “I am content to be damned with faint praise to the end of my days!”. In 1942 he was Commander of HMC Dockyard in Esquimalt, BC. In July 1943, while serving as the Staff Officer to the Naval Officer in Charge at Esquimalt, he was sent as a naval observer with the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade to observe the recapture of Kiska, in the Aleutians, from the Japanese. No RCN ships or personnel took part in the operation, although a corvette was part of the escort of the troop convoy to Adak.

After serving on over 20 British and Canadian ships, Harry Soulsby requested release from the navy and retired with the rank of Commander in 1944.

Throughout his naval career, his hobbies of painting in water colours together with wood carving served him well as a recreation whenever time and place permitted.

Following retirement in Victoria, his hobbies became his vocation. He had many commissions for wood carvings, and also excelled at painting naval ships and the realistic movement of water – his paintings on these themes sold well.

Harry Soulsby’s woodcarvings can be found in many Victoria area churches and in institutions across Canada. He worked on several items of furniture for the provincial government and for private individuals, and in addition, taught a number of students interested in woodcarving. In 1958, in an effort to improve his own carving skills, he attended the School of Wood Carving in Oberammergau, Bavaria, as a guest student. To be accepted into the Oberammergau school he had to demonstrate a high level of skill and artistry, and the experience proved to be a highlight of his life.

Despite his many achievements, Harry Soulsby remained a modest individual throughout his life. When he was asked by a colleague to prepare an autobiographical sketch of his career, he commented, with typical humour and humility: “I don’t think I ever had an official portrait taken — I was quite unimportant and Commanders were a dime a dozen then.” Despite his reticence, however, Harry Soulsby’s name lives on.

by Clare Sharpe

Museum staff member/webmaster

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum