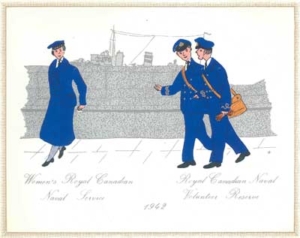

Illustration showing wartime Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) and Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) uniforms.

The following terms have been in use in the RCN for many generations –

- substantive;

- non-substantive;

- rank;

- rate;

- rating;

- promotion;

- advancement.

Unfortunately, these terms have often been misused, creating confusion. The purpose of this short article is to correctly define these terms and give examples of their proper usage, information that should prove useful when reading documents pertaining to naval personnel.

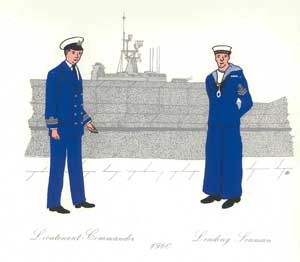

In 1910, with the formation of the Canadian Naval Service and based on the system then in use by the Royal Navy, there were two types of personnel, all male: officers and enlisted personnel. Officers held the King’s commission and wore a double-breasted jacket with eight gold buttons and gold stripes on the lower part of each sleeve. Enlisted personnel were also known and referred to as ‘ratings’ or ‘other ranks’.

As defined in subsection (xl) of King’s Regulations, Canadian Navy [KRCN], Article 1.02., rating is here defined as “the substantive status of a person in the Naval Forces other than an officer.” The word “substantive” therefore, refers only to “other ranks” and not to officers, and refers to the rank held by a given individual.

The substantive naval ranks (as noted in Article 8.12 of King’s Regulations, Canadian Navy [KRCN], Chapter 8 – Advancement of men in Substantive Rating), from lowest to highest, were:

- Able Seaman

- Leading Seaman

- Petty Officer

- Chief Petty Officer

With the rank of Ordinary Seaman included – a rank allocated to men in training – the navy had a total of five ranks for enlisted personnel.

Under the National Defence Act of 1949 that included all three armed services, the navy was required to match the rank structure of the Army and Air Force by creating two additional ranks, making seven ranks for enlisted personnel.

Petty Officer and Chief Petty Officer substantive ranks were divided into two classes:

- Chief Petty Officer First Class (abbreviated as CPO1)

- Chief Petty Officer Second Class or CPO2

- Petty Officer First Class or PO1

- Petty Officer Second Class or PO2

For Chief Petty Officers, their rank insignia consisted of three gold buttons worn on the lower part of both sleeves. Their trade badges were worn on the front of each collar. When the rank was introduced, a CPO1 wore three gold buttons with a crown above the middle button, and a CPO2 retained just the three buttons. A CPO1 and 2 wore trade badges on each side of the collar on their jackets.

A Petty Officer First Class wore two crossed anchors topped by a crown. His uniform consisted of a double-breasted jacket with six buttons. In 1949, there was no change to his rank badge. When the rank of Petty Officer Second Class was introduced, the PO2 retained the uniform he wore as a Leading Seaman, e.g. he continued to be dressed “as a seaman”, and his rank badge consisted of just the two crossed anchors on his left sleeve.

A Petty Officer Second Class (PO2) in the Royal Canadian Navy wore a rank badge with two crossed anchors on his left sleeve.

A Leading Seaman wore a single anchor on his sleeve.

Ordinary and Able Seamen had no rank badges, just a trade badge on the right arm for those so qualified.

The Officer in Charge of the RCN [Manning] Depot – there was one on each coast – was to maintain “a roster of candidates for advancement to leading rating and above” (King’s Regulations, Canadian Navy [KRCN], Chapter 8 – Advancement of men in Substantive Rating). In this case, the term ‘advancement’ would mean “promotion” to a higher substantive rank. Similarly, for misdemeanours and as a punishment, a man could be “demoted” to a lower rank.

A non-substantive rate was different from a rank. Non-substantive rates were grouped according to their duties as follows: (i) Gunnery, (ii) Torpedo, (iii) Anti-Submarine, (iv) Radar Plotter, etc., [up to] (x) Miscellaneous (Article 9.01 of KRCN, Chapter 9 – Advancement of men in Non-Substantive Rating). Such groups were then known as Trades and today in the navy they are known as Occupations. Officers did not have ‘trades’ they had ‘branches’, e.g. Medical, Pay, Engineering, Executive, and sub branches, e.g. in the Executive Branch, Navigation, Communications, Gunnery, etc.

After 1950, most trades consisted of four levels of skill and experience, the lowest being Trade Group One, the highest being Trade Group Four. Generally, a man had to be qualified by training, experience and time at sea in his rank and his Trade Group to be considered for promotion to a higher substantive rank. Before 1950, each Trade had its own system of skill and experience levels.

The badge worn by this rating in the Royal Canadian Navy shows he was trained as a Torpedo Detector.

Within each Trade there were sub divisions, e.g. in Gunnery, there was Layer Rate, Quarter Rate, Anti-Aircraft, Gunnery Instructor, etc.

Within certain trades, a Chief Petty Officer was known by his title and not his actual rank, e.g. Chief Yeoman (the senior Signalman) and Master at Arms (senior Regulator), were two such “ranks“.

To sum up, men were promoted in [substantive] ‘rank’ as shown by the rank badge worn on the left sleeve of their uniform; and were advanced in their trade [Non-substantive ‘rate’] as shown by the trade badge worn on the right sleeve of their uniform. The position on the uniform of such rank and trade badges applied to Petty Officers and below.

Prior to 1950, an individual’s Trade Group level could be visually seen by the number and position of stars on the trade badge, above or below the device used to indicate the branch. After 1950, these stars disappeared and only one trade badge design was worn by all ranks.

The chevrons worn on the left sleeve by Petty Officer First Class and below indicated a person’s “Good Conduct” time in the service. Such chevrons were not related to a man’s rank or his trade. The time in rank for the awarding of such chevrons – and the increase in pay that went with them – changed over the years.

This badge worn by a member of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) during WWII indicates the wearer was a Pay Writer.

After 1950, the first chevron was awarded for three years of “good conduct“; the second for a further five years and the third for a further five years after that, for a total of 13 years of service. Chief Petty Officers – and Ordinary Seamen – did not wear chevrons, the former because he was considered to have good character or he would not been promoted to that rank; and the latter because six months after completing basic training in STADACONA, NADEN or CORNWALLIS, he was generally promoted to Able Seaman.

During the Second World War, the same system applied to members of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (W.R.C.N.S.) They too had five ranks for enlisted personnel: Probationary Wren (basically, a recruit under training), Wren, Leading Wren, Wren Petty Officer, and Wren Chief Petty Officer. Again, the rank titles varied somewhat depending on the trade, e.g. Wren Master at Arms.

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum